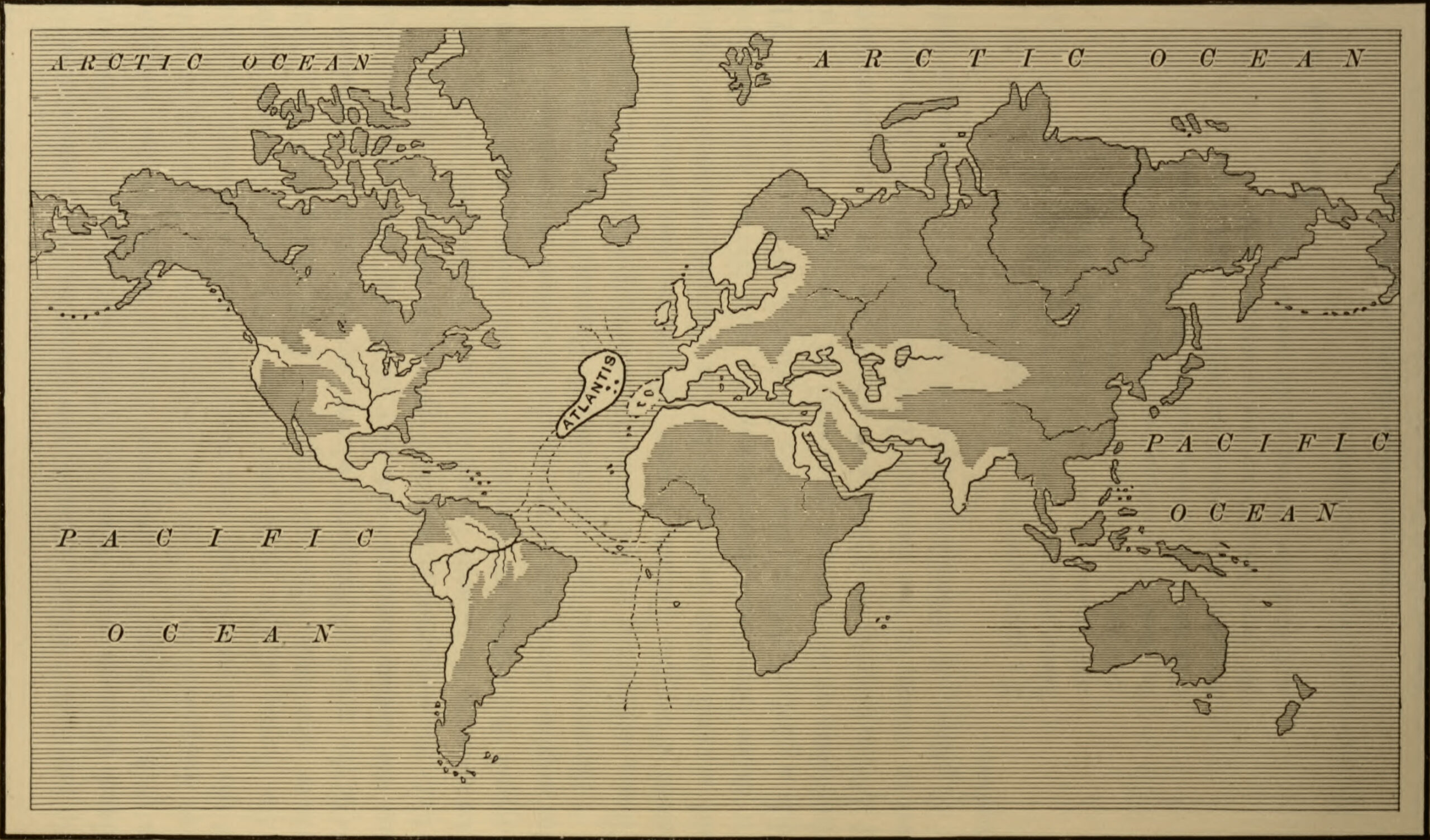

Throughout history, the legend of Atlantis has captivated the imaginations of many, sparking endless quests and debates about its existence and location. Described as an advanced and prosperous civilization that mysteriously vanished beneath the sea, Atlantis continues to elude discovery. While its exact whereabouts remain a topic of speculation, several maps have emerged over the centuries, claiming to offer glimpses into the lost city’s existence. These maps, shrouded in mystery and intrigue, have fueled the ongoing quest to unravel the secrets of Atlantis.

From ancient manuscripts to more recent cartographic works, these maps have tantalized researchers, historians, and enthusiasts with their enigmatic symbols and cryptic inscriptions. The allure of these maps lies in their potential to shed light on the elusive nature of Atlantis, providing clues to its location and the true extent of its grandeur.

Join us as we explore some of these intriguing maps and delve into the theories and controversies surrounding their authenticity. These maps offer tantalizing clues to a lost world, but are they a window into the truth about Atlantis, or mere figments of our fervent imagination?

Let’s navigate the cartographic enigmas together and unravel the secrets that lie within these maps.

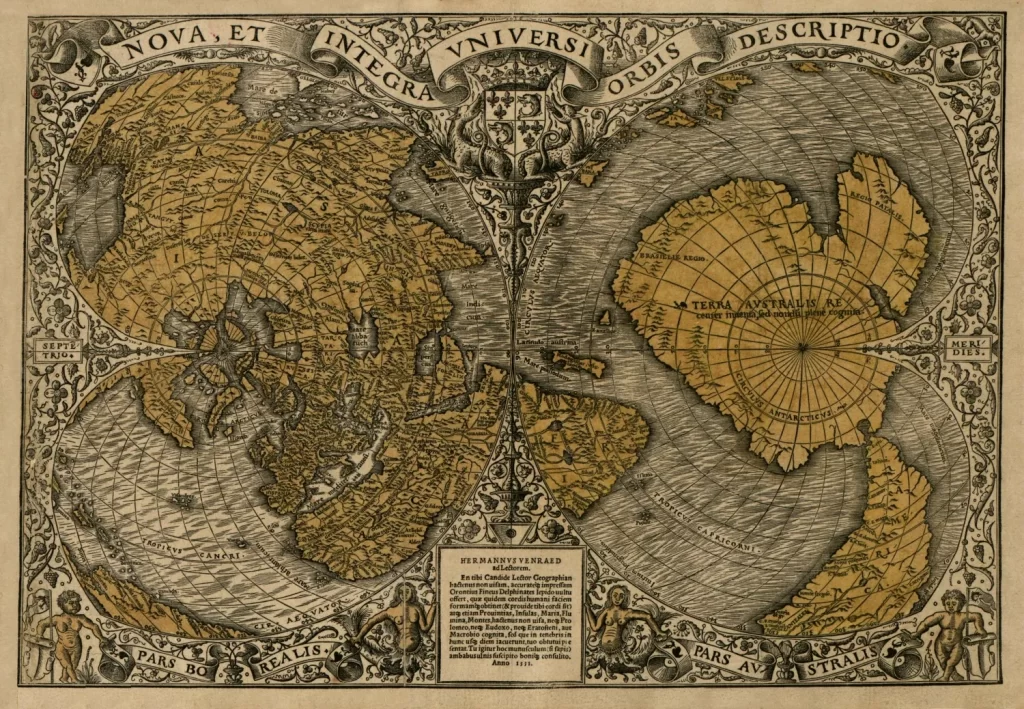

The Oronce Fine Map

The Oronce Fine Map is a historic map created in 1531 by French cartographer Oronce Fine. The map is significant because it is one of the earliest known maps to depict Atlantis. In the map, Atlantis is depicted as a large island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, located to the west of the Strait of Gibraltar.

The map shows a detailed illustration of the island, including mountains, rivers, and cities. It also features Latin inscriptions that describe the island and its history. According to the inscriptions, the island was once home to an advanced civilization that was destroyed by a catastrophic earthquake and flood.

While the map has been widely studied and discussed by historians and Atlantis enthusiasts, it is important to note that it was created during a time when cartographers often included mythical and fictional elements on their maps. Therefore, the depiction of Atlantis on the Oronce Fine Map should be viewed as a product of its time and not necessarily as evidence of the existence of the lost city.

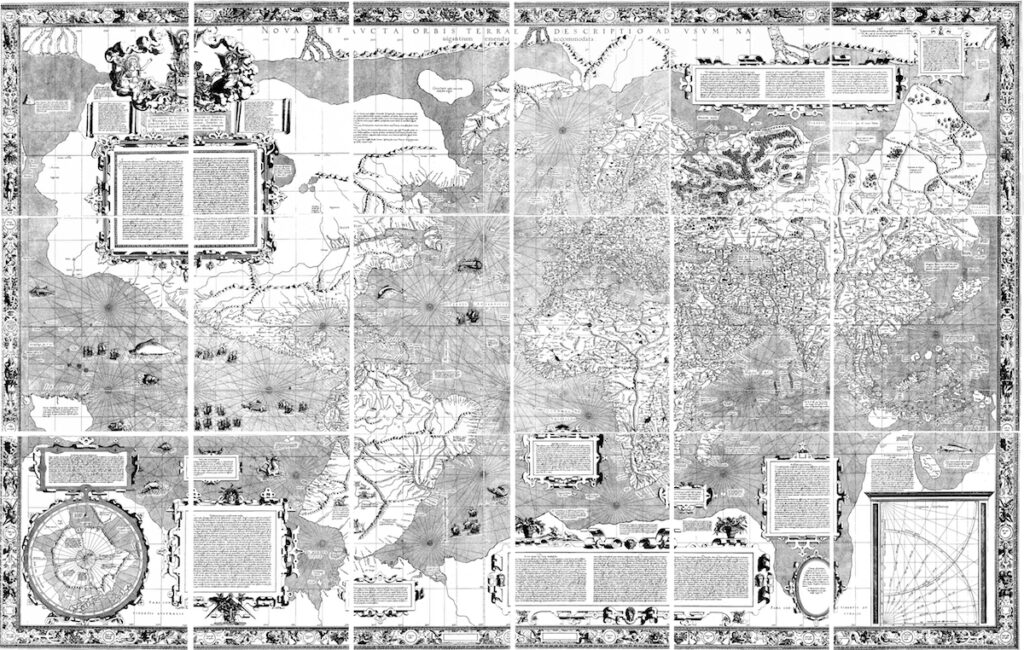

The Mercator Map

The Mercator Map is a world map created by Gerardus Mercator in 1569. It is widely regarded as one of the most influential maps in history due to its innovative use of a cylindrical projection, which allowed for accurate navigation on long voyages. However, there is no direct evidence to suggest that the Mercator Map depicts Atlantis or any specific location related to the Atlantis myth.

Despite this, some proponents of the Atlantis myth have attempted to interpret the map in a way that supports their theories. For example, some have pointed to the presence of a large continent in the southern hemisphere of the map that is not present on modern maps as evidence of Atlantis. However, mainstream scholars dismiss such claims as speculative and unfounded, arguing that the map was created before the idea of Atlantis became widespread in Europe.

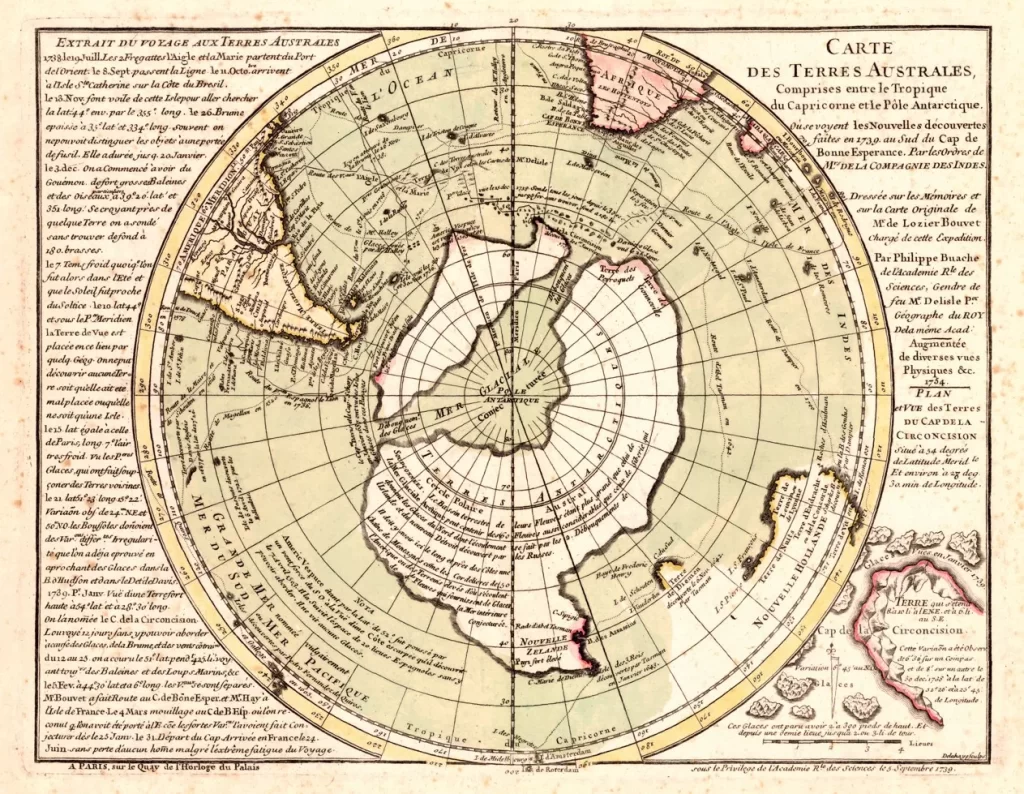

The Buache Map

The Buache Map is a map that was created by the French cartographer Philippe Buache in 1737. It is also sometimes referred to as the “Map of the Ancient World” or the “Map of the World Before the Deluge”. The map is notable for depicting several large islands in the Atlantic Ocean that are said to correspond to the location of Atlantis.

The Buache Map also shows a network of rivers and lakes in the Sahara Desert, which has led some to suggest that the map may be evidence of a previously unknown civilization that existed in the region prior to its aridification. However, many experts consider the idea of a prehistoric Sahara civilization to be unlikely.

Despite its controversial features, the Buache Map is considered an important historical document and a key piece in the history of cartography.

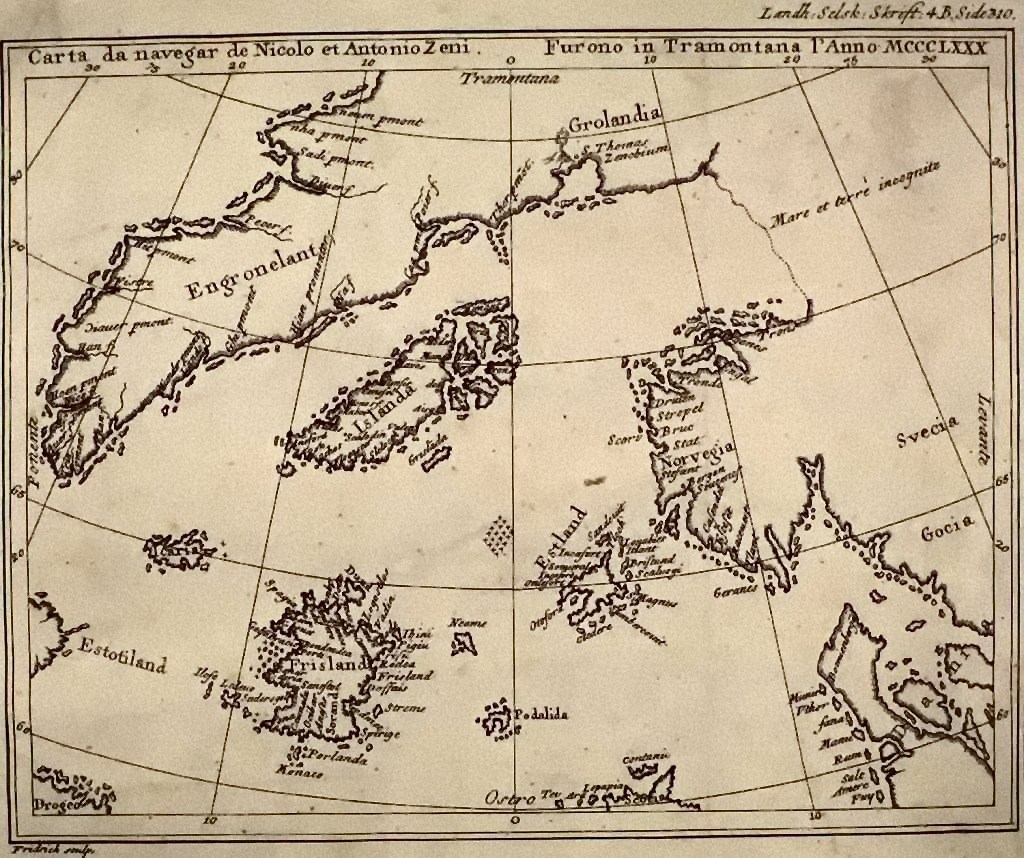

The Zeno Map

The Zeno Map is a controversial map that allegedly dates back to the early 14th century and depicts parts of North America, Europe, and Africa. It is named after Nicolo and Antonio Zeno, two Venetian brothers who claimed to have discovered the map in the 16th century among the papers of their ancestors who were said to have made voyages to the North Atlantic in the 14th century.

The Zeno Map is controversial because it includes a large island in the North Atlantic called Frisland, which some believe could be a representation of Atlantis. However, most scholars agree that Frisland is likely a mythical island that was frequently depicted on maps in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, but never actually existed.

Despite the controversy, the Zeno Map remains an important historical document because it provides a glimpse into the geographical knowledge and cartography of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. It is also interesting to note that some of the geographical features depicted on the map, such as Greenland and Newfoundland, were not officially discovered and explored until centuries after the map was purportedly made.

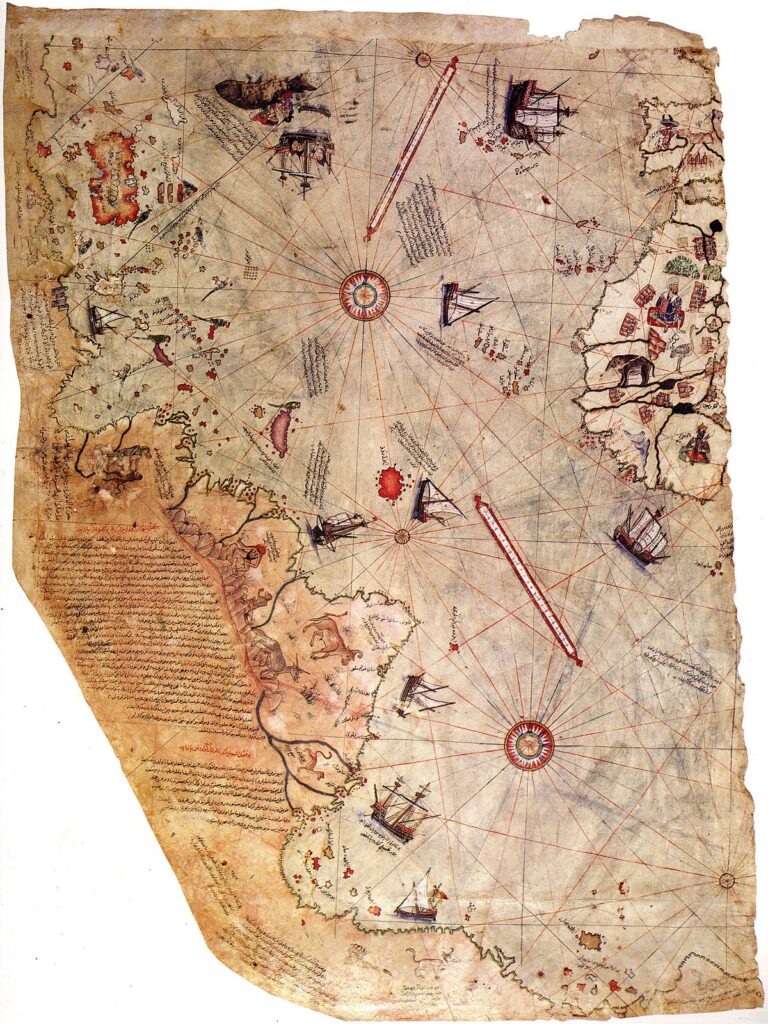

The Piri Reis Map

The Piri Reis map is a famous map created by Turkish cartographer and admiral Piri Reis in 1513. The map is notable for its accuracy in representing the coastlines of Europe, Africa, and South America, as well as its depiction of Antarctica, which had not yet been officially discovered. The map is also notable for the inclusion of annotations and notes indicating that Piri Reis used more than 20 different source maps, some of which were hundreds of years old.

One of the most controversial aspects of the map is its depiction of the coastline of Antarctica, which includes details that were not officially confirmed until the 20th century, such as the ice-free coastline and rivers. Some have argued that this suggests that Piri Reis had access to ancient or advanced sources of knowledge about Antarctica that have since been lost or suppressed.

Others, however, have pointed out that the map also contains inaccuracies and errors, particularly in its depiction of Africa and South America, and that many of the supposed “anomalies” in the map can be explained by errors in copying and transcription.

There is no definitive evidence that the Piri Reis map depicts Atlantis or any reference to it. However, some theories suggest that the map includes clues that suggest knowledge of the lost city. One such theory argues that the map accurately depicts the landmass of Antarctica before it was covered in ice, indicating that the ancient cartographers who created the map may have had access to advanced technology or information about the continent that was not available to others at the time. Additionally, some researchers suggest that the map’s inclusion of the “Mountains of Kong” in Africa, which were a fictional mountain range popularized in 19th-century literature, may be a clue that the map’s creator had access to ancient texts that included references to Atlantis. However, these theories are considered controversial and have not been proven definitively.

Despite these controversies, the Piri Reis map remains a fascinating and enigmatic artifact that continues to intrigue scholars and people alike.

Which map do you believe is the most genuine? There are other maps that some researchers believe may depict Atlantis, but their connections to the mythical city are much more tenuous and speculative. For example, some have pointed to the ancient Egyptian Turin Papyrus, which contains a list of kings and their reigns, as a possible reference to Atlantis. Others have suggested that the medieval Catalan Atlas, which features an island called “Antilia,” may have been based on the legend of Atlantis.

As we await news on Colin Trevorrow’s upcoming Atlantis movie, we thought an exploration into the evidence left behind about the lost city of Atlantis would ignite the excitement of those who may be reading. If you enjoyed this post, you can learn more about the theories surrounding Atlantis and share your own thoughts and theories in the comment sections on each page.